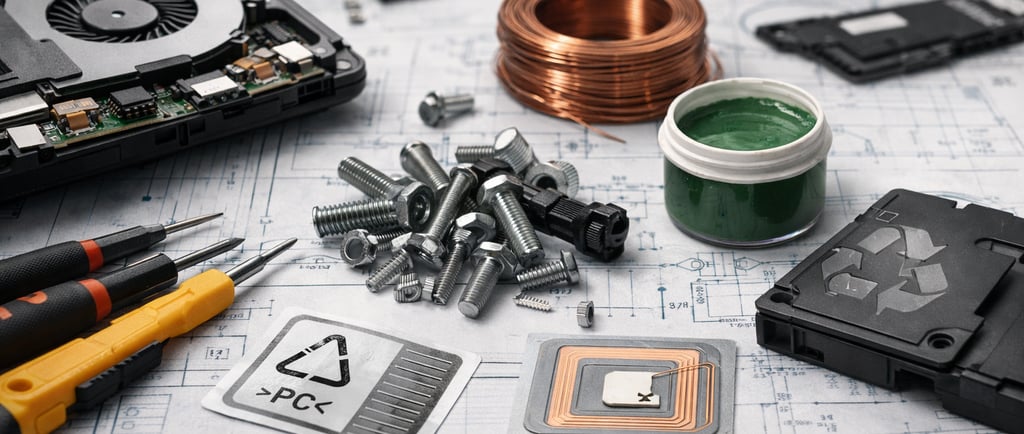

Design for Disassembly: Fasteners, Coatings, Labels

Explore how fasteners, coatings, and labels enable Design for Disassembly—the key engineering philosophy driving the circular economy, higher material recovery, and profitable product lifecycles.

WASTE-TO-RESOURCE & CIRCULAR ECONOMY SOLUTIONS

Sustainability is no longer a buzzword—it’s a critical business imperative. As global demand for resources intensifies and consumer awareness accelerates, the circular economy stands out as the only viable path forward. Companies that continue to operate under the linear “take-make-dispose” paradigm face growing economic, regulatory, and reputational risks. In this new context, design for disassembly (DfD) is emerging as a transformative mindset—one that rewires not just how we manufacture goods, but how we power entire systems of reuse and value recovery.

Strategic choices around fasteners, coatings, and labeling might appear minor at first glance. Yet, in practice, these are the granular building blocks that enable products to be easily maintained, upgraded, or remanufactured—and ultimately, to have their materials efficiently separated and reused. This holistic, systems-based approach is the foundation for futureproofing products against waste and obsolete value chains.

But how, precisely, does design for disassembly shift the economic and ecological equation? Why are the specifics of fastener types, labeling systems, and coatings so pivotal for capturing value in the circular economy? In this comprehensive guide, we’ll delve deep into the tactics, business cases, and measurement frameworks that leading organizations are using to design-out waste and keep value circulating.

What Is Design for Disassembly (DfD)?

Design for Disassembly (DfD) is not just an engineering procedure—it’s a design philosophy that foregrounds future separation and material recovery as primary criteria, on equal footing with product performance and usability. At its core, DfD challenges the notion of products as static, single-use objects. Instead, it treats every item as a temporary assembly of valuable resources, designed for adaptability and staged separation.

Key Features of DfD:

Efficient take-apart processes: DfD prioritizes the use of joints, connectors, and methods that allow products to be separated rapidly and safely at the end of use.

Lifecycle thinking: Rather than optimizing solely for initial production or functional use, DfD considers disassembly and resource recovery as integral lifecycle stages.

Material purity preservation: DfD ensures that high-value materials like metals, plastics, and composites can be separated with minimal contamination—critical for high-quality recycling and upcycling loops.

Maintainability and upgradability: Products designed for disassembly allow for easy, cost-effective repairs and part upgrades during their lifecycle.

DfD and Circular Economy Principles

The heart of the circular economy is to decouple economic activity from finite resource consumption and systematically design waste out of our systems. Design for disassembly serves this vision by:

Minimizing technical and economic barriers to repair and refurbishment.

Maximizing the number of times a product or component can enter the “reuse” or “remanufacture” loops.

Supporting next-generation reverse logistics—where streamlined disassembly equates to lower costs and higher recovery rates.

Real-world Evidence: Impact on Resource Efficiency

A comprehensive 2021 study by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation found that companies implementing DfD strategies saw a 30–45% reduction in time and labor for end-of-life processing, compared to traditional product designs. Notably, products engineered for easy disassembly demonstrated up to 90% higher material recovery rates, especially for valuable base materials like aluminum, steel, and rare earth metals (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2021).

Why Design for Disassembly Matters in the Circular Economy

The linear economy—with its focus on convenience, speed, and single-use outputs—has left a legacy of environmental degradation and resource depletion. Components are often permanently joined using welds, adhesives, or composite materials, leaving little or no path for recovery. According to the International Resource Panel, over 63 million metric tons of electronic waste was generated globally in 2022 alone—much of it unrecyclable due to design features that inhibit disassembly.

For metals-intensive industries in particular:

When coatings, adhesives, or labels introduce contamination into metal streams, they degrade both the technical and economic value of the material, complicating secondary metallurgy and sometimes rendering entire product streams unfit for recycling. This has massive industry-scale implications. For example, a single improperly coated batch of steel can lead to the downgrading of entire furnace loads, resulting in costly inefficiencies.

Guiding the Transition to Circularity

Design for disassembly flips the script: Instead of fighting against existing design flaws to recover value, businesses can build products for circularity from the inside out. Here’s how:

Facilitates repeated use, repair, and upgrade: Components that are easily accessed and swapped extend the product’s useful life significantly.

Maximizes the “inner loops” of the circular economy: Remanufacturing and reuse preserve more embedded energy and value than recycling alone.

Reduces lifecycle footprint: Easy disassembly minimizes energy and labor required to recover and purify materials.

Drives regulatory compliance: The European Union’s Circular Economy Action Plan and aggressive right-to-repair legislation are making DfD principles a baseline requirement for electronics and appliance manufacturers.

Proof Point: Automotive Sector Leadership

The automotive industry, driven by stringent end-of-life vehicle (ELV) directives in the EU and Japan, is at the forefront of this movement. According to the European Automobile Manufacturers' Association, over 95% of ELV materials are now recovered or reused, thanks in part to large-scale adoption of DfD principles in fastener choices, recyclable coatings, and standardized labels. These results highlight how DfD shifts resource recovery from an afterthought to a scalable, profitable venture.

The Three Pillars: Fasteners, Coatings, and Labels

The true power of design for disassembly emerges in the day-to-day decisions regarding how products are pieced together, shielded, and identified. Fasteners, coatings, and labels—far from being mere technical details—are the operational levers that make, or break, scalable circularity.

1. Fasteners: Enablers of Efficient Separation

Rethinking the Role of Fasteners

Historically, product designers prioritized glues, soldering, and welding for their speed and initial strength. However, these fixation methods create disassembly bottlenecks. McKinsey’s resource productivity research has underscored that mechanical fasteners—when well-chosen and strategically placed—can halve the labor costs in product tear-down by ensuring repair teams and recyclers can work faster and with fewer errors.

Best Practices for Fasteners in DfD

Emphasize modularity: Use screws, bolts, or snap-fits over permanent bonds to allow modular replacement—especially for high-wear or high-value parts.

Standardization: Streamline across product lines to limit the variety of tools and reduce operator error (e.g., using Torx or Pozidriv fasteners exclusively where feasible).

Accessibility design: Ensure that fasteners are not buried deep within assemblies, which would slow disassembly and increase the risk of damaging surrounding parts.

Minimize quantities: Research by the Fraunhofer Institute suggests a 1:1 relationship between fastener count and disassembly time—fewer, standardized fasteners directly boost efficiency.

Utilize reversible lock systems: Embrace mechanisms like snap-fits or push-to-release clips for non-safety-critical joints.

Industry Example: Dell’s Circular Laptop Platform

Dell’s best-in-class sustainability initiatives illustrate the power of reimagined fasteners. By transitioning from adhesives to screws and tool-less clips, Dell reduced the time required to disassemble laptops for repair and recycling from twenty minutes to under five minutes per unit. According to the company’s annual sustainability report, this shift doubled the recovery rates of precious metals and rare earth magnets, supporting closed-loop manufacturing and significant cost savings.

2. Coatings: Safeguarding Without Sabotage

The Double-Edged Sword of Surface Treatments

Protective coatings serve important roles—shielding products from corrosion, wear, and environmental degradation. Yet, conventional paint systems and plated finishes often become obstacles during product disassembly or recycling stages. They introduce contaminants that complicate every downstream material flow.

DfD Coatings: Key Principles & Innovations

Removability as Standard: Choose coatings that dissolve or release under controlled conditions. For example, some modern powder coatings are engineered to be removed under targeted infrared heating—preserving underlying metals and reducing hazardous chemical usage.

Compatibility in Recovery: Use coatings that do not disrupt the chemistry of large-scale recycling processes. For steel, a zinc coating within specified thresholds is far easier to recycle than chromium or cadmium, which introduce toxic byproducts.

Advance Material Labeling: Polymeric coatings infused with unique colorants or RFID-enabled spectroscopy markers help automated sorters identify and segregate coated versus uncoated components.

Data Transparency: Clearly mark coated areas on digital drawings and physical products, accelerating efficient sorting at material recovery facilities (MRFs).

Case Study: BMW’s Green Coating Revolution

BMW’s innovation in easily-strippable, eco-friendly coatings underpins its ability to remanufacture and recycle high-value vehicle parts. These coatings are designed to break down with mild solvents or specific heat treatments—avoiding the need for abrasive or chemical stripping that would damage both materials and the environment. As a result, BMW has increased end-of-life recovery for aluminum and high-grade steel components, cutting processing costs and supporting its ambitious goal of a 50% recycled content target by 2030.

3. Labels: The Deciders of Disassembly

Labels decide whether disassembly stays niche or becomes normal

Fasteners and coatings decide whether a product can come apart. Labels decide whether anyone can take it apart at speed, sort it correctly, and recover value without guessing.

That sounds minor until you look at the scale of what the world is throwing away. In 2022, the world generated 62 billion kg of e-waste, and only 22.3% was documented as formally collected and recycled. The same research flags roughly US$62 billion in recoverable resources left unaccounted for in that one year. ITU+1

Those numbers do not point to a lack of recycling theory. They point to a throughput problem. Sorting, identification, and routing decisions must happen in seconds. Labels are the mechanism that makes seconds possible.

What a “DfD label” actually needs to do

A circular label is not a marketing sticker. It is an operations tool that answers a few non-negotiable questions the moment a technician or recycler touches the product.

It must tell you what the material is, with enough precision to avoid cross-contamination. It must tell you what is on the surface, because coatings and treatments can change downstream chemistry. It must tell you what the risky bits are, because batteries, fluids, and electronics change safety procedures. Then it must point you to the right disassembly approach, because a wrong first move breaks parts and kills reuse value.

When labels fail, two expensive things happen. The first is labour inflation, because trained people spend time diagnosing what should have been obvious. The second is quality collapse, because mixed streams get downgraded, rejected, or routed to lower value processing.

Physical labels and digital labels serve different moments

Physical marking wins at the point of action. A sorter, repair tech, or dismantler needs a quick read. That is why etched, stamped, moulded-in, or laser-marked IDs outperform glued labels in real industrial conditions.

Digital identity wins across time. It stores service history, part revisions, replaced modules, and compliance information that buyers and regulators may later demand. It also allows traceability at end of life, which matters more every year as product rules tighten.

The most reliable approach combines both. You give the human a visible cue and you give the machine a scannable key.

Where label standards already exist and why they matter to DfD

Many companies reinvent marking and end up with internal codes that nobody outside the brand understands. That breaks circularity the moment the product leaves your service network.

Plastics already have a mature path. ISO 11469 specifies a uniform marking system for plastics products to support decisions on handling, recovery, or disposal. ISO 1043-1 defines standard abbreviated terms for basic polymers and aims to prevent multiple terms for the same plastic. Together, they exist for one reason: stop confusion in the recovery chain. ISO+1

Electronics supply chains also rely on standardised material declarations, because restricted substances and material transparency drive compliance and processing decisions. IEC 62474 specifies procedures and content for material declarations in the electrotechnical industry. That kind of upstream data becomes far more valuable when you pair it with clear product and component identity at end of use. IEC Webstore

If you build DfD without a standardised marking and declaration approach, you make every downstream partner pay the “translation tax.” They will pay it in time, errors, and lower bids for your returns.

Digital Product Passports turn labels into compliance and market access

DfD used to be a voluntary advantage. In the EU it is moving toward market expectation, because policy is shifting from waste management to product design.

The European Commission describes the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation as a tool to improve product sustainability through circularity, durability, recyclability, and related requirements. This direction matters because it pushes product identity and product information into the core of market access. European Commission

Batteries show the clearest timeline. The EU Batteries Regulation states that from 18 February 2027 certain batteries placed on the market must have an electronic record, the battery passport, and it sets the requirement in Article 77. EUR-Lex

This is not a distant future concept. Reuters reported Volvo launching an EV battery passport ahead of EU rules, with a simplified QR-based view for owners and a deeper version for regulators, and a cost of about $10 per vehicle to produce. Reuters

That is the direction of travel. Product identity becomes a structured record. Labels become the doorway to that record. Disassembly becomes easier when the record tells you what you are looking at.

High-speed sorting is becoming camera-first, not human-first

Labels do not need to be visible ink to work. They can live as machine-readable codes that survive rough handling and still route material correctly.

Packaging is an early proof point for this idea. HolyGrail 2.0 describes digital watermarks as imperceptible codes detectable by high-resolution cameras in sorting facilities, enabling packaging to be sorted into the right streams based on embedded attributes. That is the same logic DfD needs for complex product categories with mixed materials and high contamination risk. HolyGrail+1

Standards that make DfD repeatable across teams and supply chains

DfD fails when it stays trapped inside product engineering. You need shared rules that connect design, procurement, service, and recovery.

In the built environment, ISO 20887:2020 covers design for disassembly and adaptability in buildings and civil engineering works and gives guidance for integrating these principles into design. It is a strong reference because construction has long lifetimes and large material stakes, and it forces discipline in access, documentation, and future change planning. ISO+1

At the organisation level, ISO 59004 provides vocabulary, principles, and guidance for implementing circular economy practices, and ISO 59020 sets requirements and guidance for measuring and assessing circularity performance through a standardised process of data collection and calculation using indicators. These two move circularity from “project” to “management system.” ISO+1

Policy pressure is also forcing alignment. The European Commission notes the Directive on repair of goods was adopted on 13 June 2024, entered into force on 30 July 2024, and Member States must apply it from 31 July 2026. That timeline changes product decisions now, because design cycles and parts planning run years ahead. European Commission

DfD business models that pay for the extra thought upfront

DfD only scales when it improves unit economics. It does that by increasing retained value, reducing handling cost, and opening revenue lines that linear design blocks.

Repair and service margin becomes easier to defend when access is fast and low-risk. Products that open cleanly cut labour time and reduce collateral damage during repair.

Trade-in and buy-back programs become easier to price when identification is reliable and grading is quick. Labels and modular joints reduce the “unknowns” that force conservative buy-back offers.

Remanufacturing becomes a second production line when disassembly yields intact modules and predictable inspection steps. Renault Trucks states remanufacturing can take up to 85% less raw materials and 80% less energy, and that in 2022 remanufactured parts used in its repair network saved over 1,900 tonnes of CO2. That is the kind of claim finance teams understand because it links materials, energy, and outcomes. Renault Trucks

Service-based ownership models also reward DfD because you carry lifecycle cost. Signify’s Schiphol case describes a model where the customer buys the light rather than the luminaire and luminaires can be returned at end of life for reuse or recycling. The same case cites a 50% reduction in electricity consumption and 3,700 new LED luminaires installed. DfD matters here because return and reuse only work when products are easy to repair and refresh. Signify

Automation and robotics push DfD from “nice” to “necessary.” Apple reported that its Daisy robot can disassemble iPhones at a rate of 200 per hour. Robotics like that only works when the product family behaves predictably enough for repeatable disassembly. DfD increases that predictability. Apple

Measurement that proves DfD is working

DfD needs metrics that engineering trusts and finance funds. Use measures that tie directly to labour time, yield, contamination, and resale value.

Start with disassembly time. Track minutes to reach the top value components and minutes to separate the product into clean material streams. Time is the common currency across repair, remanufacture, and recycling.

Track tool complexity. Count how many tool types you need and how often you must switch tools during the tear-down. Every additional tool adds training cost, error risk, and cycle time.

Track fastener variety, not just fastener count. A product with fewer fastener types is easier to service at scale because technicians make fewer mistakes and work faster.

Track non-destructive removal yield. Measure what share of targeted components come out intact. This one number predicts whether you will make money in refurbishment and remanufacture.

Track contamination and downgrade rates in recovered streams. For metals, coatings, adhesives, labels, and embedded non-metals can push a stream into lower-value processing. For plastics, mixed polymers and additives have the same effect.

Track first-pass sorting accuracy. If you need manual escalation too often, your labels and product identity are not doing their job.

Then translate these into outcome numbers that executives care about. Cost per unit processed. Revenue per unit recovered. Reuse and remanufacture share versus shred-and-sort. Where possible, add circularity scoring that makes comparisons easier across product lines.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Material Circularity Indicator is a free Excel-based tool for measuring how circular a product’s material flows are, and the Foundation publishes the methodology behind it. Use it when you need a consistent product-level measure that supports design reviews and portfolio reporting. Ellen MacArthur Foundation+1

How to implement DfD without turning it into a slow committee process

Run DfD like a throughput project, because that is what it is.

Pick one product family where you already see returns, repairs, or warranty volume. Film the disassembly. Time it. Note where damage occurs. Identify what forces tool switching, what hides connectors, and what contaminates the output streams.

Then redesign only the biggest blockers first. In most categories, the biggest blockers are buried fasteners, permanent bonding where you need access, coatings that foul recovery, and missing or non-standard identity on parts.

Bring recyclers and service teams into the same room early. Ask one simple question and do not negotiate it. What do you need to know in 30 seconds to route this correctly. Then bake that into markings, digital identity, and service documentation.

Lock your DfD targets into design reviews the same way you lock safety and compliance targets. If a change increases disassembly time or increases stream contamination risk, treat it as a cost increase. Because it is.

DfD is the operational edge in a world of rising waste and tighter rules

DfD wins when it treats end of use as a designed phase, not a disposal problem.

Labels are the pivot point. They cut guesswork, speed decisions, and protect material quality. They also connect products to digital records that regulators and buyers increasingly expect, including battery passports from 18 February 2027 in the EU. EUR-Lex

The waste numbers make the stakes obvious. 62 billion kg of e-waste in 2022, and only 22.3% formally collected and recycled, is a signal that current systems cannot keep up. Better design and better identity must carry part of the load. ITU+1

DfD is not a philosophy you hang on a wall. It is a set of design decisions that show up as faster repair, higher reuse yield, cleaner material streams, and better economics across take-back and remanufacture.